Animal agriculture is a polluting industry. Around 16.5 percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and nearly 60 percent of food production emissions come from meat.

A lot of this is due to ruminant animals, mainly cows, producing methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas. Manure management and the conversion of forests to pasture and to grow crops to feed farmed animals also contribute to meat’s climate impact.

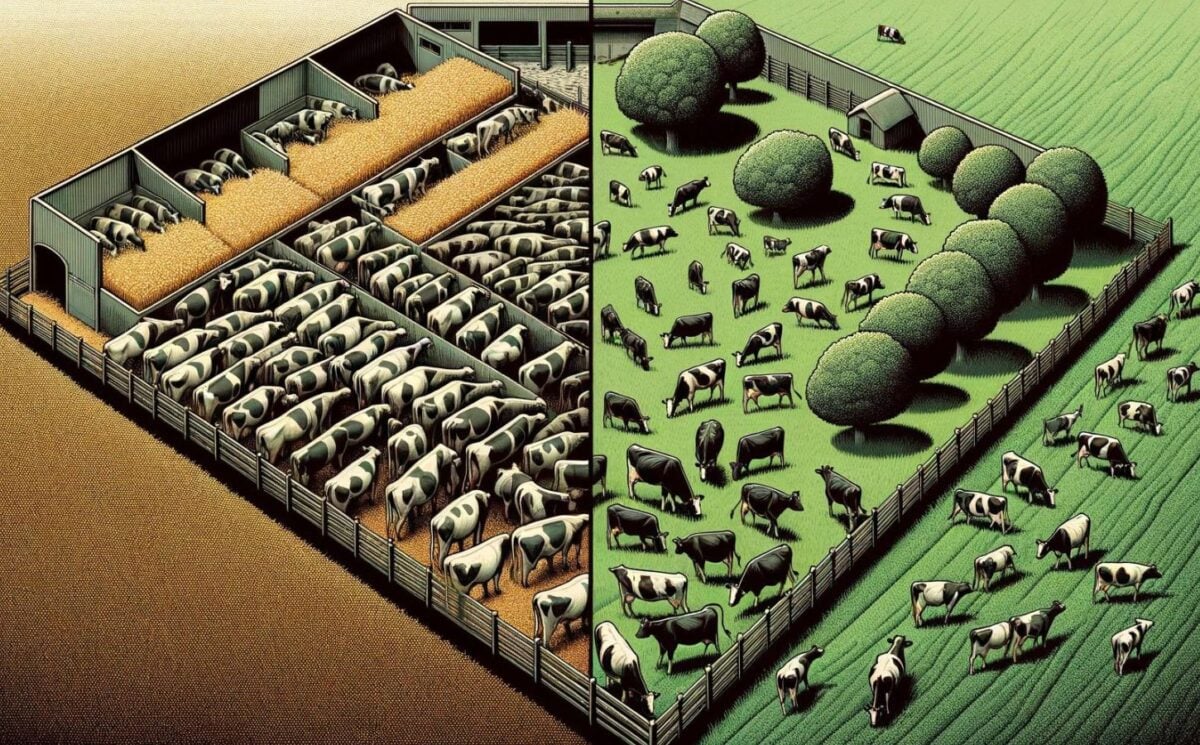

There are two options for bringing down the emissions from meat production. One is to significantly reduce meat consumption and the number of animals being farmed. The other is to make animal farming more intensive, since intensive farming is more efficient.

Climate scientists favor the first solution. They say that eating plant-based diets, especially in wealthy countries, is a key way to cut global GHGs. But the meat industry and some governments are pushing for further intensification of animal farming instead.

Rising demand

Since the 1960s, meat production has more than quadrupled globally. The biggest increase has occurred in Asia, where production rose 15-fold over the past 50 years. This trend is likely to continue as meat consumption is projected to rise by 14 percent by 2030. Demand is growing particularly in developing nations where incomes are rising.

Animal farms have also become more intensive over this time, housing many more animals in smaller spaces. It’s estimated that more than 90 percent of farmed animals are now kept in factory farms.

At the same time, a small number of corporations have ever more control of the meat industry. They buy up smaller farms and control the supply chain too, from production of animal feed to distribution of food. Companies including Cargill, JBS, Vion, and Smithfield (owned by Chinese WH Group) are what the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) calls the “Meat Majors” of the “Global Meat Complex.”

Emissions intensity and absolute emissions

The number of animals on a farm doesn’t tell you how emissions intensive it is. Farms with more animals kept at higher densities can have lower emissions intensity than farms with fewer animals, even if absolute emissions are higher.

But what’s the difference between emissions intensity and absolute emissions? Emissions intensity is about the amount of emissions per “unit,” such as per kilo of meat or liter of milk. Absolute emissions refers to the total emissions attributable to a farm or meat company. So an intensive dairy farm with hundreds of cows would have higher absolute emissions than a small dairy farm, but would be more efficient – i.e. less emissions intensive.

Animal agriculture in wealthy countries tends to have lower emissions intensities than lower-income countries. This is due to differences in feed, management practices, and animal breeds.

But big meat producers have huge absolute emissions. IATP found that the top 20 meat and dairy companies together emit more GHGs than the whole of Germany.

Reducing emissions in developing nations

Organizations such as the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) promote increased agricultural productivity, including in animal farming. This is because of the growing human population and the projects rise in demand for animal products.

At the same time, these organizations recognize the need to reduce emissions from meat and dairy production. To do that, they say that more animal products need to be produced more “sustainably.”

“Sustainable intensification” is the solution put forward by FAO, WRI, and others for developing nations. This is because animal farming supports many livelihoods and is currently a key source of protein for food-insecure communities in the Global South.

FAO Roadmap

The FAO set out a roadmap for sustainable intensification following the last UN Climate Summit COP28 in December 2023. Among the recommendations in the roadmap are better breeding techniques to make animals more productive and swapping farming cows for chickens. The FAO also promotes feed additives for cows such as seaweed to lower methane production.

The roadmap has received criticism from environmental groups and researchers. Dr Matthew Hayek, Professor of Environmental Studies at New York University, wrote a paper about how such a strategy means reduced emissions from cows but an increased risk of disease spread, such as avian flu, from more intensively farmed chickens. Groups including ProVeg highlighted how the roadmap ignores the negative impacts of industrial animal agriculture, such as water and air pollution and poor animal welfare.

Reducing emissions in developed nations

The FAO roadmap acknowledges that reducing consumption of animal products in wealthy countries will cut emissions. But it advocates some of the same strategies for reducing meat emissions in the Global North as in the Global South.

These strategies include feed additives and making “biogas” from animal manure. The meat industry has already embraced these methods, seeking to further reduce emissions intensity without reducing the amount of meat and dairy being produced.

In wealthy countries like the US, these “solutions” also depend on further intensification of animal farming.

Cows and methane

Much research is being done into different feed additives which could inhibit methane production in cows’ digestive systems. Seaweed, essential oils, and even daffodils, are all being tested to find effective, safe additives.

But feeding these to cows tends to require them to be in feedlots, where their diets can be controlled. Meanwhile, the majority of the methane they produce is when they are grazing on pastures. This means that in practice emissions savings using feed additives could be smaller than those reported in feeding trials, or that cows will need to spend more of their lives in pens and barns.

In the dairy industry, there is already a trend towards further intensification. A Viva! investigation revealed that “zero-grazing” systems are on the rise in the UK. Viva! believes these intensive farms that keep cows inside all day now account for around 20 percent of the UK dairy industry.

Eat chicken instead

Consumers in wealthy countries have also been encouraged to eat chicken instead of beef, since emissions from chickens are lower. Even some environmentalists have promoted this idea on climate grounds. Increasing demand for chicken meat has led to a proliferation of intensive chicken farms in countries such as the UK. This has led to worse welfare, higher zoonotic disease risk (as Hayek describes), and severe environmental pollution from chicken waste.

Though chicken farming emits far less GHGs than farming cows, it is still around three times as carbon intensive as plant foods like tofu.

Feeding intensively farmed animals

Intensification of animal farming impacts what they are fed and how agricultural land is used. Cows that graze on pasture all their lives produce more emissions and require more land. If they are raised more intensively or “finished” on grain in feedlots, this reduces their emissions and land requirements.

One research paper states that “Intensification of beef production thus presents an important opportunity for land sparing.”

However, the paper also notes that intensification of animal farming means that more feed must be produced for the animals. If feedcrops are grown on deforested land, this can create emissions that can “outweigh the on-farm emissions savings.”

It’s for these reasons, that the meat industry is looking to novel and alternative feed sources for intensively farmed animals as another way of lowering its emissions. These sources include industrially farmed insects, food waste, and animal by-products.

Emissions savings of intensification versus less meat

Intensifying animal farming can help to reduce agricultural emissions, but brings with it many additional negative impacts.

FAO has estimated emissions reductions for each of the interventions it suggest in its “sustainable intensification” strategy. The biggest reduction, at 20 percent, would come from increasing productivity. Other interventions such as improved manure management would bring minimal climate gains. The emissions reductions estimates are also based on many assumptions, such as that improvements in feed are “also applicable in extensive systems.”

Reducing the consumption and production of animal products has significantly more potential to reduce emissions. This is because land freed up from animal farming could be rewilded, which would help to store carbon.

One research paper found that wealthy countries could cut their agricultural emissions by almost two-thirds by going more plant-based. This would release an area of land larger than the entire European Union from agricultural use. If it were restored to a natural state, it could capture the equivalent of 14 years’ worth of global agricultural emissions.

Research by Oxford University has found that a widespread adoption of vegan diets would slash food-related emissions by 70 percent.