On March 20, the final installment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth assessment report (AR6) was released. Its message is clear: we have this decade to get a good start on major changes to our food and energy systems to avoid climate and ecosystem-induced societal destabilization.

The good news is we largely know what we need to do. The bad news is some industries are working overtime to keep these solutions under wraps.

IPCC’s AR6 Synthesis Report

The comprehensive document draws on the findings and recommendations of hundreds of scientists from the IPCC’s three working groups. Put simply, the report covers updates on the physical science of the climate crisis (WGI), ways to adapt and be more resilient (WGII), and the state of climate mitigation (WGIII).

Once again, the IPCC report urged for transformational changes to society to avoid passing further climate crisis thresholds. And again, there was one key area that was largely left out of the conversation: the global food system. In particular, meat and dairy production in comparison to plant-based foods.

Meat industry accused of interfering with IPCC report, removing mention of plant-based diet

Over the past five years especially, there’s been an increased awareness that paradigm-shifting food system change will be key. However, the IPCC reports are growingly vague in their outline of what a balanced, eco-friendly diet is:

“Balanced and sustainable healthy diets and reduced food loss and waste present important opportunities for adaptation and mitigation while generating significant co-benefits in terms of biodiversity and human health (high confidence)” (p.74).

What do they mean by balanced and sustainable diets? Hidden in the footnotes they describe it as a plant-predominant diet:

“Balanced diets feature plant-based foods, such as those based on coarse grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds…” (p.74)

But according to leaked documents from earlier AR6 reports in 2021, and now from Scientist Rebellion, initial wording here was:

“Plant-based diets can reduce GHG emissions by up to 50 percent compared to the average emission-intensive Western diet.”

Pressure from beef lobbyists allegedly brought on this change, as well as the inclusion of the recommendation to eat “animal-source foods produced in resilient, sustainable, and low-GHG emissions systems” with little evidence of how or where that’s happening.

There’s no glaringly new evidence listed in the synthesis report. But here are the five food system takeaways.

Latest IPCC report: 5 key takeaways

1. The importance of methane

Cutting methane is the fastest and most effective way to slow the climate crisis. In fact, it has the potential to reduce global warming by over half a degree. For perspective, we’ve warmed 1.2 degrees Celsius (°C) since the pre-industrial period, and are quickly approaching the Paris Agreement’s limit of 1.5°C.

Why do these small degrees matter? Even fractions of degree increases over 2°C will result in increased species collapse, more intense droughts, storms, and floods (that increase the number of climate refugees), and war and conflicts over limited resources.

A theme of the IPCC AR6 reports is this urgency to address methane. That’s because the planet will warm equally from methane and carbon dioxide over the next 20 years. And reducing warming quickly will help avoid climate thresholds from being passed, some irreversibly so.

Methane levels have risen to 262 percent above what they were in pre-industrial times. And the pace at which they are increasing each year is now greater than any other period in history.

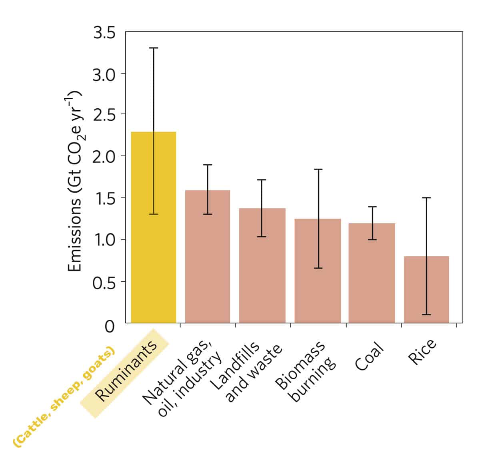

Where does methane come from?

There are many sources of human-caused methane. But farming animals for food is the largest, contributing 32-40 percent, slightly above other equally unnecessary sources like natural (fossil) gas. At more than four billion (and counting) farmed ruminants, and animal agriculture now leading in methane emissions, it shows where our first focus should be.

Methane is likely undervalued in a number of ways, too. Firstly, measuring methane on a 100-year vs. 20-year timeline devalues it by 2.5 times. This more relevant 20-year timeline is now being used in New York State, but is a debatable method for long-term use. Secondly, animal methane emissions may be 39–90 percent higher than bottom-up measurement models predict. This is especially true in the United States due to how intensive animal farming is.

Despite these concerns, a majority of countries’ climate pledges do not include methane reduction goals for animal agriculture, a win that’s celebrated by lobbyists in the beef industry. This indicates a major bias towards certain industries at the cost of environmental breakdown.

2. The impact of deforestation

The Amazon is one of the most important climate buffers left on the planet. If we continue to allow it to be deforested for ranching, it’s projected to reverse from an overall carbon drawdown sink to a net emitter. More than three million different species also call the Amazon home, making it one of the most diverse areas on Earth.

Protecting these forests of mature trees is far better than temporary tree plantations, sometimes non-native, that are often part of sketchy carbon credit schemes that are allowing some of the biggest emitters to greenwash.

Cattle ranching is the number one cause of deforestation in every Amazon country, accounting for 80 percent of current deforestation. And this should accompany every IPCC statement related to tropical deforestation.

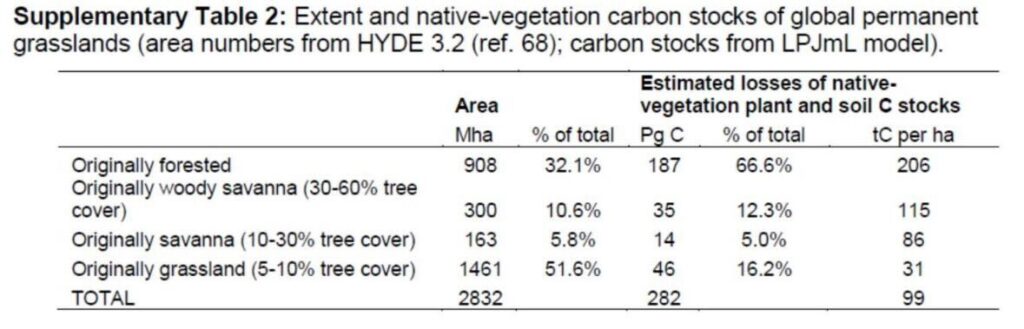

3. Destruction (and potential) of natural ecosystems

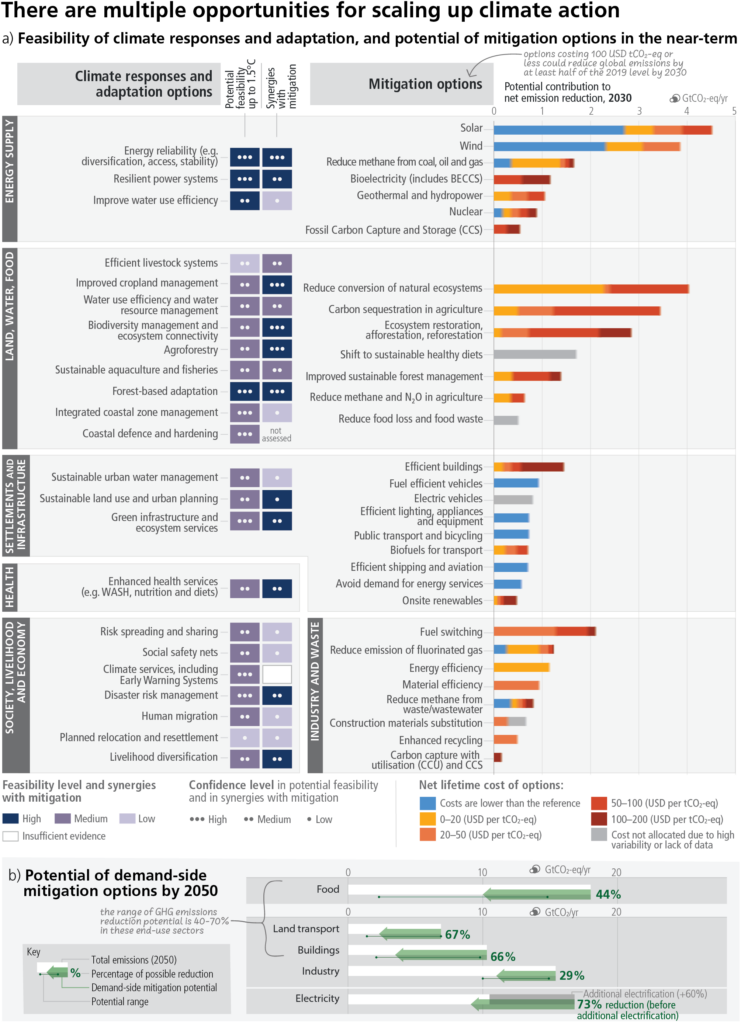

Natural ecosystems are at threat from food system pressure expansion, mostly from ranching, feed crops, biofuels, and fishing. Reducing conversion of natural ecosystems actually has higher climate crisis mitigation potential than wind energy, and almost as much as solar.

We need all of these solutions, but perspective is important. These native ecosystems offer the best and most affordable and achievable methods of carbon removal. While the IPCC lists other approaches (like regenerative agriculture), these are niche, poorly defined, and highly susceptible to greenwashing. They could even result in more emissions, not to mention other environmental trade-offs like a major increase in land use per yield.

“Unsustainable agricultural expansion, driven in part by unbalanced diets, increases ecosystem and human vulnerability and leads to competition for land and/or water resources (high confidence)” (p.15).

While there’s a spectrum to the impacts of farmland on ecosystems, removing cattle grazing increases almost all types of abundance and diversity of native flora and fauna. Moreover, broadly speaking, there’s 25-75 percent less soil organic carbon in land used for food production vs. wild untouched ecosystems.

While food overall is responsible for at least one-third of all GHGs (25-42 percent) that doesn’t include the opportunity to drawdown carbon with rewilding back to native ecosystems. And, significantly skews policy focus elsewhere.

4. Food waste crisis and meat production

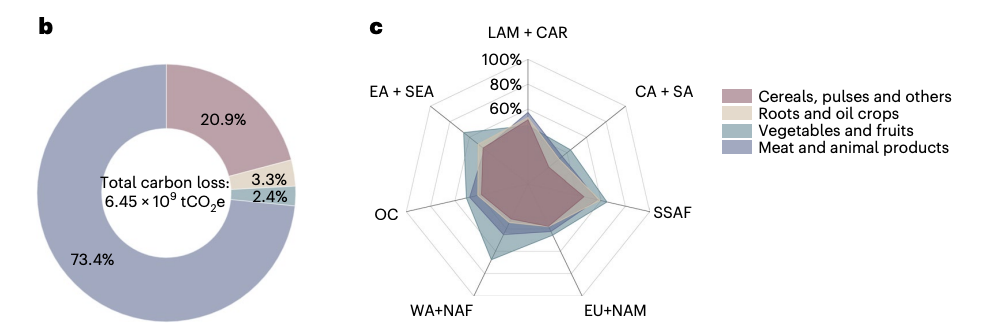

Reducing food waste will be key. By far the largest source of food waste, not technically categorized under IPCC’s analysis of food waste, is the ~90 percent of calories lost when growing crops to feed to animals to produce meat. This feed-conversion loss is the biggest food waste crisis.

Even under technical parameters though, this new research, as covered by Carbon Brief, shows only 2.4 percent of global supply emissions from food waste come from fruits and vegetables. Of the ~19Gt of CO2 from global food loss and waste in 2017, the vast majority (~11.5 Gt CO2) comes from wasted animal products.

As such, authors recommended a 50 percent meat reduction to directly mitigate food waste.

5. Lack of media coverage

The latest IPCC report installation acknowledges a distinct lack of media coverage surrounding these issues.

“Policy and media coverage is uneven across sectors and remains limited for emissions from agriculture and feedstocks” (p.19).

New research surrounding media coverage and public awareness of the links between animal-sourced food and the climate emergency drives home just how significant the problem is. Researchers found that “in the US, UK, and English-language EU media… only 0.5 percent of articles on climate mentioned meat or livestock as a source of emissions.”

Final thoughts

Without transformational changes to our food and energy, most of which would also increase wellbeing globally, global warming of 3.2°C is projected by 2100. This will be an absolute devastation to children today, and future grandchildren.

While the nearly 8,000 pages from the IPCC AR6 reports can be seen as bleak, we now know more than ever about what we need to do. While feeling overwhelmed or doomed is a risk, we should be mad and channel that energy to the many real scientific solutions that exist to make life far better for current and future generations.