Is coconut oil healthy? Or is it simply the best of a bad bunch?

You can’t walk through a supermarket these days without seeing something made from coconuts. Coconut water, yogurt, milk, cheese — even coconut jerky. It’s an “it” food if there ever was one.

But is coconut oil good for us? And what about its reported tie to unethical monkey labor?

Is coconut oil healthy?

Once shunned for its high saturated fat content, coconut oil is now found in health food shops and supermarkets across the globe.

Most vegetable oils (soya, olive, sunflower and rapeseed oils) contain less than 20 percent saturated fat. Butter contains more than 50 percent. But coconut oil clocks in at a whopping 86.5 percent saturated fat. So how is that healthy?

Coconut nutrition

Like all plant foods, coconut is cholesterol-free. Although it is a fruit, coconut flesh has a very different nutritional content from other fruits. A third of the flesh is composed of fat; nearly 90 percent of which is saturated. That’s not great news. Saturated fat increases cholesterol, which increases the risk of heart disease.

Desiccated coconut (coconut flesh that has been flaked and dried) contains is about 66 percent fat. A similar amount is found in hazelnuts, almonds, and Brazil nuts. But most of that is polyunsaturated fat that can lower the risk of heart disease in moderation.

Where coconut oil is a health concern, its fiber content is a health boost. The fiber content in desiccated coconut is two to three times higher than in nuts. Some studies suggest that coconut flakes lower LDL “bad” cholesterol because of the fiber content.

Coconut fiber

Processing coconut to produce oil, though, strips away this protective fiber.

A 1980s study on coconut oil described how Pacific Islanders, who ate coconut at every meal, had lower than expected cholesterol levels. Even with all that cholesterol. And, heart disease was rare. They had low intakes of salt, sugar, and cholesterol, and consumed a healthy amount of fibre, plant sterols, and omega-3 fats.

They also had an active lifestyle and used little tobacco. When the islanders moved to New Zealand and reduced their saturated fat intake, their intake of cholesterol, junk food (simple, instead of complex carbohydrates) and sugar increased and so did their risk of heart disease. This provides evidence that the whole diet and lifestyle can have a profound effect on health.

Is saturated fat unhealthy?

Major health organizations, including the World Health Organisation, the American Dietetic Association, the British Dietetic Association, the British Heart Foundation, the National Health Service, the US Food and Drug Administration, and the European Food Safety Authority, agree that saturated fat is a risk factor for heart disease.

Most saturated fat in the average UK diet comes from fatty meat, poultry skin, sausages and pies, whole milk and full fat dairy products (cheese, cream, butter and ghee), lard, coconut oil, palm oil, pastry, cakes, biscuits, sweets, and chocolate.

Saturated fat drives up cholesterol levels and too much cholesterol can lead to fatty deposits that not only clog the arteries and slow blood flow but can break apart and cause a heart attack or stroke.

Cochrane Reviews are internationally recognized as the highest standard in evidence-based science. A 2012 Cochrane review found that reducing saturated (animal) fat, but not total fat, reduced the risk of heart attack and stroke by 14 percent (1).

Are all saturated fats equal?

The saturated fats, lauric, myristic, and palmitic acid, are found in meat, dairy products, eggs, palm, and coconut oil. They all raise cholesterol levels but not to the same extent:

- Myristic acid: found in palm kernel oil (not to be confused with palm oil), coconut oil, butter and other animal fats, is the most potent ‘bad’ cholesterol-raising.

- Palmitic acid: found in palm kernel oil, butter, cheese, milk and meat and raises cholesterol less than myristic acid.

- Lauric acid: comprises about half the fat in coconut oil. Found in smaller amounts in human breast milk, cow’s milk and goat’s milk. Has around one-third less cholesterol-raising power than palmitic acid.

Medium and long-chain fats

One of the claims made for lauric acid from coconut oil is that is it broken down and used by the body differently from other saturated fats because it is made of medium-chain as opposed to long-chain fats. Most fats in animal products are long-chain saturated fats that are made into cholesterol or stored as body fat. Medium-chain fats are transported directly to the liver from where they supply energy directly to the heart, brain, and muscles. Well, that’s the theory anyway.

Studies on coconut oil and cholesterol have produced conflicting results. Some studies show that medium-chain fats increase HDL “good” cholesterol but others show they also increase LDL ‘bad’ and total cholesterol to the same extent as palm oil. Other studies found no effect on HDL, LDL, or total cholesterol. Medium-chain fats have also been found to increase plasma triglycerides in the same way long-chain fats do.

One possible explanation is that when the diet contains mostly medium-chain fats (when coconut oil is used in preference to unsaturated vegetable oils), some medium-chain fat may be diverted into the long-chain route leading to the production of cholesterol and fat deposits. This provides a compelling argument for not limiting your fat intake to just coconut oil.

Furthermore, medium-chain fats make up less than half of coconut fat, nearly a third is made up of the long-chain saturated myristic and palmitic acids (the major fats found in red meat) which raise “bad” cholesterol levels. The rest consists of small amounts of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Criticism of coconut studies

Many of the health claims made for coconut oil are a mixture of anecdotal evidence, pseudoscience and poor reporting of a limited number of flawed studies (conducted over short periods of time with small numbers of participants).

The results are not yet significant enough to prove long-term benefit. Enthusiasts appear to have extrapolated the potential benefits exaggerating them beyond anything the science can confirm. Whereas research supporting the benefits of polyunsaturated plant oils (particularly monounsaturated and omega-3 fats) are well-established.

The claim that coconut oil may help treat or slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease is largely based on anecdotal evidence and animal experiments which bear no relevance to humans. In a recent review in the British Journal of Nutrition it was concluded that: “It must be emphasised that the use of coconut oil to treat or prevent AD [Alzheimer’s disease] is not supported by any peer-reviewed large cohort clinical data; any positive findings are based on small clinical trials and on anecdotal evidence; however, coconut remains a compound of interest requiring further investigation (2).”

What’s the smoke point?

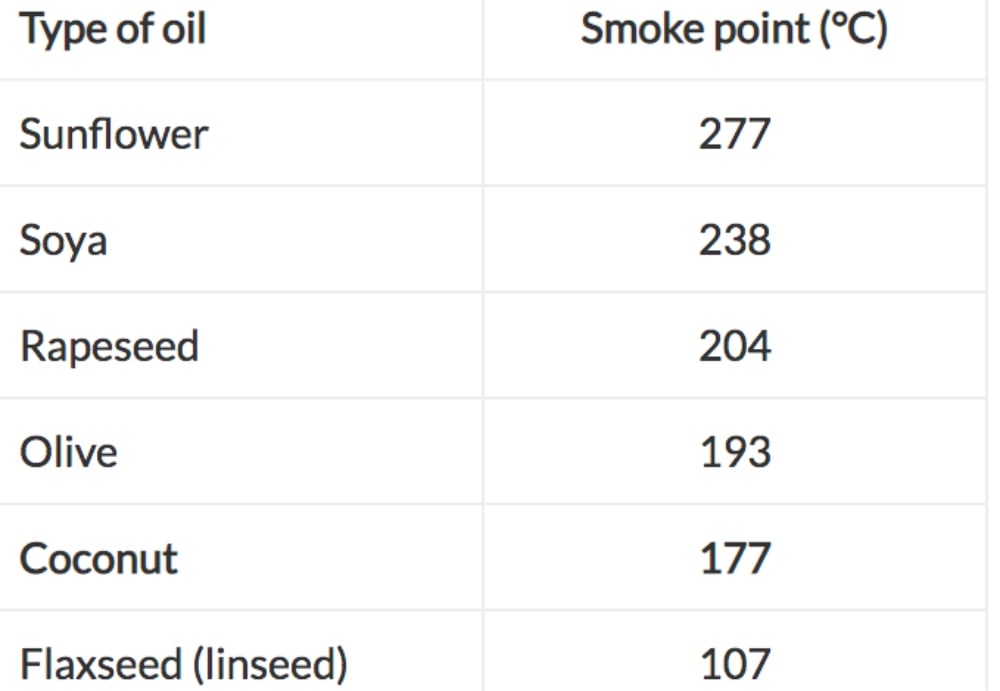

Another selling point for coconut oil is the reputed high smoke point (that’s when the fats in the oil break down or oxidize, creating harmful free radicals). However, many other oils have a higher smoke point. In fact, coconut oil has a relatively low smoke point compared to other commonly used cooking fats.

No magic bullet

Like most “magic bullet” food and health stories, there may be some truth in the claims made for coconut oil. Coconut oil is healthier than butter, lard and hydrogenated, trans-fat containing fats, but it is unlikely that including additional coconut oil in the diet would be beneficial. Medium-chain fats in coconut oil may raise HDL “good” cholesterol.

However, they can also raise LDL “bad” and total cholesterol. Whereas replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats (found in vegetable, olive, flaxseed, and rapeseed oils, as well as nuts and seeds), have been shown to increase HDL, lower LDL and improve overall cholesterol levels all at the same time.

Walter Willett MD, Chair of the Department of Nutrition at the Harvard School for Public Health sums it up nicely: ”Most of the research so far has consisted of short-term studies to examine its effect on cholesterol levels. We don’t really know how coconut oil affects heart disease, and I don’t think coconut oil is as healthful as vegetable oils like olive oil and soybean oil, which are mainly unsaturated fat and therefore both lower LDL and increase HDL (3).”

It is the total diet coupled to healthy lifestyle that is most important in disease prevention. It is better to eat a diet with a variety than to concentrate on individual foods as the key to good health. Coconut oil’s HDL-boosting effect may make it “less bad” than its high-saturated fat cousins (butter and lard), but it is not the best choice of oils to reduce the risk of heart disease. You are better off replacing saturated fats with healthier unsaturated vegetable oils such as olive oil and rapeseed oil for cooking and flaxseed oil for sauces and dressings.

Coconut farming

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, global demand for coconuts is growing at 10 percent a year. Most are grown by small-scale farmers across Asia Pacific and despite the growing coconut trade, many live in poverty or very basic conditions as the price they’re paid for their harvest is dictated by processors.

As a response, many initiatives have been launched to help coconut growing communities prosper and farm in a sustainable way. If you have a favourite brand of coconut products, check out their website as many have details of their projects. Always look for a Fair Trade label as that should ensure farmers get a proper wage.

Is coconut oil ethical?

Coconut harvesting is an extremely contentious issue. In Thailand and some other Asian countries, pigtailed macaques are trained to do the harvesting. They’re used because they are more efficient than people and their labor is “free.”

According to recent reports, 99 percent of Thai coconuts may be harvested by these monkeys who are either taken from the wild or bred for the purpose and trained. Some say the monkeys are kept as family pets. But investigation footage and photos suggest grueling working hours, with monkeys fainting of exhaustion. They spend much of their life tied to a leash, and experience rough handling from humans.

A Fair Trade certificate doesn’t mean a monkey didn’t pick your coconut. So it’s best to make sure your coconut product manufacturer has a policy in place that ensures only humans harvest their coconuts.

Coconuts taste great but all the ethical issues and saturated fat make them a not-so-ideal food.

And unless you live in Southeast Asia, coconut products will have to travel a long way to reach you. That uses fossil fuels and needs packaging.

Organic and Fair Trade coconut products support sustainable farming without the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. And they also provide fair wages for the farm workers.

Most importantly, research the company from which you’re buying coconut products to learn about their ethics.

References:

(1) Hooper et al., 2012. Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5:CD002137.

(2) Fernando et al., 2015. The role of dietary coconut for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: potential mechanisms of action. British Journal of Nutrition. 22 1-14.

(3) Willet W, 2011. Ask the doctor; coconut oil [online]. Available from: www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/coconut-oil. Accessed June 18, 2019.

This article has been republished with permission from Viva!